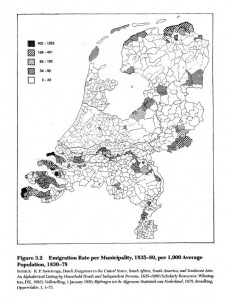

uit: Faith and Family, Dutch Immigration and Settlement in the United States, 1820-1920 by Robert P. Swieringa 2000

The province of Groningen ranked second (behind Zeeland) in its emigration rate 41 per 1000 average population. More than 8,700 persons emigrated in the years 1830-80. The three cash grain regions of northern Groningen led in the emigration. The Hunsingo area was dominant with 5,900 emigrants (68 percent), the Fivelingo area had 1,000 (12 percent), and the Westerkwartier on the Frisian bor der had only 800 emigrants (9 percent).

Three fourths of Groninger emigrants before 1880 left in the years after 1865, when the northern Netherlands experienced an agricultural revolution. Farmers mechanized rapidly and adjusted their operations to utilize the new machines more efficiently. Steel plows, threshing machines, steam tractors, combines, hay rakes, reel driIls, and other implements offered tremendous advantages to large-scale, cash crop fanners who had to increase their efficiency in order to compete in world markets against cheaper grain from North America, Ukraine, Argentina, and else- where. By 1885 Groningen led the nation in horse-drawn threshing machines, steel plows, row seeders, and steam tractors.

The consolidation of farms increased the pressure on land prices, left few openings for new farmers, and threw farmhands out of work. The Reverend Bernardus De Beij, who in 18681ed hundreds of Groningers to Chicago from his Seceder con- gregation in Middelstum, described weIl the dismal prospects in the homeland in a letter written from Chicago

There is a great number of farmer’s sons and daughters in Groningen who possess considerable capital, and who gladly would like to buy a fann in accordance with their available capital. However, that is not possible because all the land is occupied. When a farm comes up for sale there are twenty who would like to buy, but only one can become the owner. Tlle price is driven so high that in order to live himself, he later needs the sweat and blood of day laborers, family, buyers, and tradesmen. Others wait for the death of the grey landowner.

For many agriculturalists therewas no altemative but to migrate to Dutch cities or leave for America. Groninger emigrants went almost exclusively (96 percent) to the U nited States; they were second only to Frisians in their America-centeredness. Virtually all hailed from the countryside. Agricultural workers comprised three quarters (77 percent) of all emigrants, skilled craftsmen totaled 17 percent, and white-collar persons only 6 percent. Eighty percent of the Groningen emigrants were of middling economic status, which was the highest proportion of any province. The national average among all emigrants was 65 percent.

The notabie feature of the early emigration from Groningen was that it was spearheaded by Seceders, followers of the fiery preacher of Ulrum, Reverend Hendrik de Cock, who had sparked the Secession of 1834 throughout the northem Netherlands. At a time when Seceders numbered less than 6 percent of the province’s population, 70 percent of all Groningen emigrants in the 1840s were Seceders. In the 1850s this dropped to 17 percent, but after the Civil War Seceders again numbered 30 percent. One in five of the Seceder families left primarily to gain religious freedom and the right to found free Christian day schools for their children. Roman Catholics, another religious minority, totaled 13 percent of the Groninger pioneers. Only 14 percent of the emigrants before 1850 were members of the predominant Hervormde Kerk, but thereafter two thirds were Hervormden.

The early emigrants were an older population of financially stable craftsmen and small farmers. One third were craftsmen and a quarter were farmers. Over 80 percent were of middling economic status, and 11 percent were wealthy. A quarter of the early emigrants were subject to the head tax on income, compared to only 7 percent among later emigrants. This was clearly a religious protest movement of comparatively well-off families. The emigration pattems from tlle five geographic regions of the province present sharp contrasts. The Hunsingo area along the North Sea coast had the richest, most productive clay soil in tlle Netherlands. The agricultural revolution struck early here and with great impact on the farm workers who were hired as needed and worked by tlle season at best. These excess hands emigrated to America in large numbers.

Of Hunsingo emigrants, 58 percent were rural day laborers, and anotller 26 percent were small fanners and farmhands. Thus, 84 percent were agricultural workers. Half of tlle Hunsingo emigrants were single adults, who had to delay marriage because they could not obtain steady work or a fann in order to support a wife and family. Almost to the last person, Hunsingo emigrants went to the United States. Religiously, 64 percent were mernbers of the Hervonnde Kerk, a very large 29 percent were Seceders, and 7 percent were Catholic. In the province in 1849, the Hervonnde Church claimed 81 percent ofthe population, Catholics 7 percent, and Seceders 6 percent.46 Thus Seceders were overrepresented almost five-fold and Hervonnde Church mernbers were underrepresented by 25 percent.

The preferred destination of Hunsingo emigrants was western Michigan, where two thirds (66 percent) settled. Chicago attracted 17 percent, 4 percent went to Lafayette, lndiana (a Groningen fann community), and 4 percent went to wiscon- sin. The Chicago Groningers, who settled near the city center on the near west side, hailed mainly frorn Uithuizermeeden, Usquert, Middelsturn, Eenrum, and Baflo. Emigrants frorn Leens, Uithuizen, Warffum, Bedurn, Adorp, and Ulrurn preferred western Michigan. Most Lafayette Groningers came frorn Kantens, Een- rum, Leens, and Ulrum.

Fivelingo, a rich cash grain area comparable to Hunsingo, spanned the area northeast of the city of Groningen to the seaport of Delfzijl. lts emigration charac- teristics are similar to those frorn the Hunsingo except for several notabIe differ- ences. Again, 55 percent ofthose departingwere rural day laborers and 19 percent were farmhands and small farmers. Together, the fanners and fann workers included 76 percent of all emigrants, compared to 84 percent in the Hunsingo. The difference was that Fivelingo emigrants numbered more skilIed craftsmen- 21 percent compared to 13 percent in Hunsingo. Unmarried singles comprised 39 percent of Fivelingo emigrants, 10 points less than in Hunsingo. Religiously, emigrants frorn the two are as had the same proportion of Calvinists-two thirds Hervonnde and one third Seceder.

Over 99 percent of Fivelingo emigrants went to the United States. The favored destination for two thirds was western Michigan, especially Grand Rapids. Chicago was preferred by one third. The municipalities of ’t Zandt and Stedurn were the most important emigration fields. More than one third of ’t Zandt emigrants and over one quarter of Stedurn emigrants settled in Chicago where they comprised most of the residents in the “Groninger Hoek.”

Frorn the third sea-clay region, the Westerkwartier on the Frisian border south of the Lauwerszee, only 766 emigrants left, led by the municipality of Grijpskerk. Emigration began later here than elsewhere in Groningen; only 3 percent lef t before 1865 and 97 percent frorn 1865 through 1880. More than half (57 percent) were Seceders. This was the highest percentage of any region of the N etherlands and more than ten times the proportion of Seceders in the province.

The Westerkwartier Seceders were strongly influenced to leave by their fellow dissenters who had emigrated earlier frorn Hunsingo and Fivelingo. The agricul- tural revolution also reached the Westerkwartier later and this delayed the onset of the out-migration. Again, two thirds (74 percent) of all emigrants were fanners and fann laborers, with 18 percent skilIed craftsmen and 8 percent in white-colIar posi- tions. They were slightly poorer than other Groningen emigrants; 22 percent were on the public dole and 71 percent were of middling status, compared to 17 percent and 76 percent, respectively, from Fivelingo and 12 percent and 85 percent, respectively, from Hunsingo.

The United States received 97 percent of Westerkwartier emigrants, led by western Michigan, mainly Grand Rapids, with 68 percent. Iowa gained 15 percent and Chicago 13 percent. Grijpskerk and Zuidhom emigrants were the most focused-they went al most entirely to western Michigan. Those from Oldehove also favored Michigan, but a few went to Iowa and Chicago. Aduard emigrants went mostly to Chicago.

The Oldambt and Reiderland areas on the German border differed froJQ the sea clay regions. The soil was sandy and less fertile and farms were smalIer. Rye was the chief crop and it was produced for local consumption, although some wheat was grown on clay soils to the north but with crop rotation. The pressure to emigrate in the Oldambt was minimal and only 6 percent of the Groningen emigrants origi nated here. Nearly half of these (44 percent) were skilIed craftsmen and 12 percent were in wl1ite-colIar positions. Thus fewer than half were in farming, which con- trasts sharply with the clay area where 75 to 85 percent of the emigrants were in farming.

The Oldambt emigration began in eamest twenty years earlier than elsewhere. Nearlyone third of its emigrants through 1880 departed in the 1840s. Religiously, 33 percent were Seceders, 9 percent were Catholic, and 5 percent Jewish. All three groups were overrepresented, the Seceders by six-fold. One in five Seceders expressed a desire for religious liberty; these pious folk had suffered much for the faith. The Oldambt emigration was an exodus of tradesmen more than farmhands, and religious discontent played a major role in instigating the emigration. In economic standing, 78 percent were of middling status, 10 percent wealthy, and 12 percent needy. The United States was the destination of 94 percent, which was only 5 points less than among clay-soil emigrants. Again, Grand Rapids was the primary destination (77 percent), with Chicago the home of 10 percent. The municipalities of Wildervank, Nieuwe Pekela, and Hoogezand were the main places of origin of those bound for Grand Rapids.

The provincial capital, Groningen City, sent out only 487 emigrants, 6 percent of the total, although it held nearly 17 percent of the total provincial population. This was a unique migration, because 42 percent held white-colIar positions and 51 percent were craftsmen. Over one half we re singles, of whom almost one quarter were women. Thirty-nine percent were wealthy – more than six times the average among all emigrants from the province. And a very high 43 percent did not settIe in the United States, compared to 5 percent or less among those from the countryside. Religiously, 71 percent were Hervormde, 16 percent Catholic, 7 percent Seceder, and 6 percent Jewish. Thus, the proportion of Catholic and Jewish emigrants from Groningen City was unusually high, as was the percentage of craftsmen and wl1ite-colIar workers. The emigration from the city was thus split between Catholic and Reformed tradesmen going to America and Reformed white-colIar types seizing job opportunities in the Dutch East Indies, Netherlands AntilIes, Surinam and Curar;ao, and South Africa. Of the city’s emigrants to the United States, half chose western Michigan, a quarter Chicago, and a fifth Buffalo.

Emigration from the province of Groningen was dominated by farmers from the clay regions, led by the Hunsingoarea. By contrast, Oldambt and the capital city had only minimal emigration and that mainly of white-collar workers, many of whom opted for the Dutch oversea so many rural emigrants ended up in Chicago, Grand Rapids, Muskegon, Lafayette, and other urban places, is remarkable. They desired farmland but simply could not afford to buy it, at least not until they had worked for some years. The magnet of the cities was jobs. City folk also needed to be fed, so many Groningers specialized in truck farming on rented land at the periphery of the growing cities.