The story of Heero Smit

On April 22, 1944, an important man for the Germans was shot dead by the resistance (NSB policeman Keyer). He was a traitor of the worst kind, and the Germans were furious that they had lost such an important informant. This occurred in Bedum, about 5 kilometers from our village. We all lived in tension, as we were sure that something would happen.

In church that Sunday morning, it was already whispered that a raid was coming. About fifteen youths in the dangerous age left the church, accompanied by the minister. However, nothing happened that day in our village; absolutely nothing. In a neighboring village, a man was shot dead. In fact, there was already a sense of relief among us.

The following night (the night of April 25) would, however, lead to the largest and most effective raid in the northern Netherlands. More than a thousand soldiers, Grüne Polizei, and Feldgendarmerie surrounded four villages. These villages were clearly their target. They acted like beasts. Four young men were shot dead in cold blood. They searched every home from top to bottom.

I was not afraid. After all, I had an exemption because I had to work to support my mother (a widow) and sister. They wouldn’t take me. But I was wrong. I was indeed taken to the village café, where many prisoners were already in line. Twelve young men were taken, two of whom never returned.

After the raid, we were driven to the city of Groningen in a stolen car, facing the unknown.

In Groningen, we were brought to the police station at Martinikerkhof. The Grünen left and handed us over to the Landwachters. We were given some food and were thoroughly searched. All

any somewhat valuable items were taken from us. In the evening, we received a piece of bread and a cup of substitute coffee. Bales of straw were brought in for us to sleep on. Sleeping was impossible. There was no space and too little straw. We lay like pigs in a sty.

At half past five, we were ordered to get up. We had to assemble. The Grünen were also present again, with their rifles at the ready. We were counted, and the numbers matched. Several names were read aloud.

They had to stand against the wall. We feared the worst, but nothing happened. What enormous tension! The Grünen surrounded us, and in military marching tempo, we left the police station. We were one hundred and fifty men from four villages. We headed toward the main station and were loaded onto the train. To where?

The final destination was Amersfoort, notorious as the city with the Vernichtungslager, where people had to wheelbarrow stones on wheelbarrows with square wheels. Amersfoort had become a concept during the occupation. A place of terror, torture, and hunger. In short, a place of horror. Camp Amersfoort was known as the camp in the Netherlands where the most deaths occurred. It was rightly a Durchgangslager, as out of the 35,000 prisoners that camp counted, about 20,000 were transported to Germany. It was a heavily guarded camp.

We had to walk half an hour from the station and then we sluggishly entered the camp. The barrier fell behind us, and we were in the clutches of the enemy.

The first night was not very comfortable, but we were still alive and had come through it without a scratch. That was something. The food was meager. Yet, we would later look back on it with nostalgia.

Because we were considered hostages, we received special treatment. We could keep our clothes and were not shaved bald. The lice were rampant. On our heads and in our clothes, those filthy creatures were everywhere.

After more than two months, the message came that we would be put on transport. We received a transport letter, which we could send home. With that, our fate was sealed.

The next day, I was shaved bald anyway. I hardly recognized myself. On July 7, we were to leave. Everyone was quite tense. But there was also curiosity and a sense of adventure about what would happen. I had hardly been out of my village, let alone the country.

On the evening of the last day, we received a suitcase of clothes and a final letter from home. After that, one last check. The numbers were called out (we no longer had a name).

We had to pass by Pool Kotälla, who checked to see if the photo on the new passport was correct. We were given a whole loaf of white bread, half a pack of butter, and a chunk of cheese. That was our food for the journey.

In rows of four, we left the barracks. Kotälla gave the last hits with his stick, and with our heavy suitcases, we stumbled outside. There stood a complete army of SS soldiers to escort us to the station. Many of us had to leave their heavy suitcase behind because they could no longer carry it. Fortunately, I had enough strength to keep my belongings. After walking for over an hour, we arrived at the station. The train doors opened, and we were shoved in like cattle. Finally, we could catch our breath.

At half past four in the morning, we left Amersfoort station, heading for the Third Reich. We traveled in a decent passenger train and had spacious seats. Not bad for someone like me, who had never gone further than the city of Groningen. And all for nothing! My sense of adventure resurfaced, and I even enjoyed the journey. I saw a lot of natural beauty. Mountains and valleys, beautiful. I was in awe. Quite different from the flat coal fields in our village. We also saw much destruction. Signs of English and American bombings.

Through Rhein, Osnabrück, and Hameln (where we saw a big plaque honoring the rat catcher), we finally arrived in Braunschweig. The train stopped. This was my final destination.

With about a hundred men, we trudged away, tired and hungry. We dragged our suitcases along. Where were we headed?

To a barrack settlement, about five kilometers outside Braunschweig. A walk of over an hour. The place was called Mascherode.

The accommodation was not bad. We had a room with fourteen men. Each had a cot, a wardrobe for our clothes, a table with chairs, and a wood stove. We received a sack to put straw in. We could sleep on that. We also got two thin blankets. In July, that was enough, but in the winter, it was far too little to keep warm.

We were given a dry slice of brown bread and a pot of sour-smelling soup. This was our first introduction to the sour German bread and the notorious cabbage soup (just water with a few pieces of cabbage). We ate it with pleasure. The meal disappeared quickly, but the feeling of hunger remained.

I was assigned to work in a car factory (Büssing). We were not beaten, but the food was horrendously poor. We were always hungry.

In the mornings, we had to report at four o’clock and then walk an hour to the factory. There we would get a slice of bread, cabbage soup at midday, and that was it. The work was not hard for me. Braunschweig was heavily bombed. We, as prisoners, were not allowed in most shelters. Those were for the Germans. If you were in such a shelter when the bombs were falling, it was terrible inside too. One would curse, another would scream for his mother. There was much praying and shouting. My luck was that I knew no fear. I stood or sat and listened to it all.

After the bombings, we had to clear rubble and bodies. That was no fun at all.

As we had to walk two hours a day and the footwear was poor (instead of socks, we had rags on our feet), my feet became sore and inflamed. I could not disinfect anything, and the infection grew worse. A large swelling on my shin and blood poisoning landed me in the infirmary. A Russian doctor cut the swelling open without anesthesia. There was talk of amputation of my leg at my bedside.

In the evening, there was another major air raid alarm. Everyone ran to the shelters. I stayed behind. I fell asleep, and the next morning, I could stand on both legs again. It was a miracle. My leg did not need to be amputated.

In April 1945, we were liberated. Together with three other boys, we walked back to the Netherlands through Germany. Just keep walking and sometimes hitching a ride in a military truck. Along the way, we sometimes received food from kind citizens. Occasionally, we stole some fruit and drank milk from cows in the fields. It was a grim journey with our starving bodies. But home was calling.

In Limburg, we crossed the border. We were disinfected and deloused. We found shelter in a café, where we were doing well. We could not yet go north. There the war was still ongoing.

When it was finally possible, we hitched rides and walked again. Transportation in the Netherlands was still completely paralyzed. In Assen, we stayed overnight with family from one of the boys. After that, we took a horse and cart to Groningen. The last leg was to my village, Zuidwolde. No one recognized me. A skeleton with big eyes, in rags. That’s how I stumbled into the village. Someone from the Internal Armed Forces brought me home. The suffering was not over yet. I was very weakened. My leg was still open, and I returned home in the middle of the church struggle (the liberation). The family came to welcome me, but no one listened to my story. Everyone seemed to have experienced worse things. I remained silent while the uncles argued over the church. Deeply disappointed, I walked into the fields and thought: “Is this it then? From one war into another?”

Hiking Tour Jan Peter

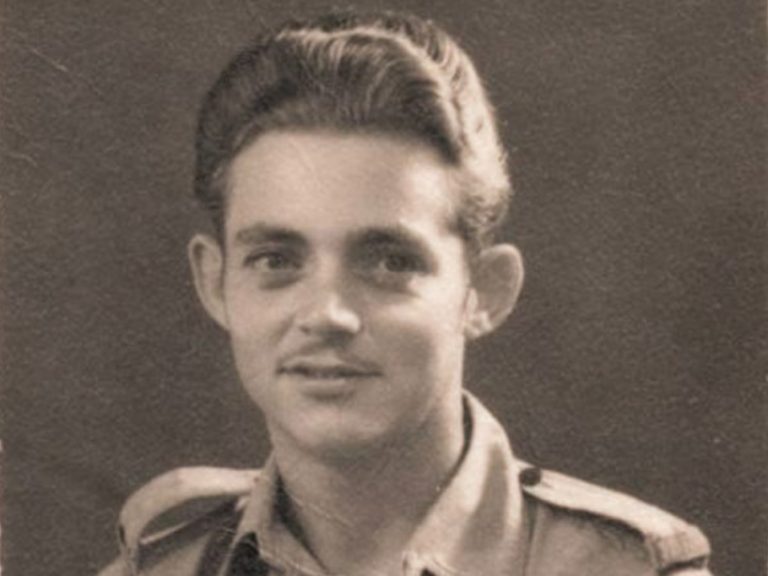

On April 25, 1944, my father, Heero Smit, was arrested at the age of 18 during a raid by the German occupiers.

He was taken, via Camp Amersfoort, to Mascherode (near Braunschweig). There, he had to work in the factories of Büssing. After a year (April ’45), the Germans capitulated and my father was free.

Since there was no transportation, he walked back to the Netherlands (severely emaciated, extremely fatigued, and injured) “simply” heading west. After a few weeks, he arrived in Venlo.

Only after the northern Netherlands was liberated could he return to Groningen.

My father survived World War II. In 2010, he lost the battle against Lewy Body at the age of 84. As a tribute, I want to undertake the walking route from Mascherode to Venlo once more. I will cover this over 400 km from August 1 to August 13, 2022. With this walk, I was able to make a significant contribution of over €2,500 to the research of Alzheimer Nederland.

During my adventure, I wrote a short story about my experiences and thoughts every day on Instagram. I also took many photos of the things I saw along the way.

I have now compiled all these stories and photos into this book.

Enjoy reading,

Jan Peter Smit